Avoid missed opportunities and faulty assumptions

A common ripple effect of the shared services or central HR support approach is experienced when businesses don’t have a full understanding of the issues, challenges and expectations of a particular country, geography or region. This means heavy expectations are placed on central resources to fully understand the implications of global decisions at a granular level and to respond to local issues.

In addition, the subtleties of employment and human capital practices can be ignored or overlooked as part of the strategic business objectives. This results in missed synergy opportunities or inaccurate cost of expansion calculations, since human capital decisions have been based on faulty assumptions.

Supported by Grant Thornton research[i], we know that expansion into foreign markets remains a vital ingredient to fuel business growth. Businesses need to make sure that they understand the different cultures and implement solutions to attract the best local talent. To do this, they need to successfully navigate any legal or financial pitfalls by staying informed and accessing the right expertise in a timely manner.

For Michael Monahan, assistant managing principal for people and culture and the principal-in-charge of the Northeast human capital practice at Grant Thornton US, this is all familiar territory.

“We deal with a broad array of human capital issues around the world and have even been engaged to support clients dealing in war-torn nations. We recently provided support to a client seeking to provide services and employ people on the ground. They were struggling to work out how to pay these people and even what currency to use.

“Another client was trying to expand its operations into a new country and reached out to us just before it inadvertently tripped the national hiring requirements for the country. We helped them navigate this through our in-country member firm being able to provide timely and applicable guidance.

“We also routinely work with clients – whether during a transaction or when exploring new approaches to total rewards – to try to understand and diagnose how local cultures value particular elements of the overall total rewards programme. For example, some employees prefer restricted stock grants and others prefer options, others prefer higher fixed wages and either low or even no equity. Some businesses also struggle with aligning performance with pay while others find it to be natural to provide transparent feedback to colleagues.

“These cultural differences can be significant. When they are overlooked they tend to create more problems and have frequently been the cause of missed financial targets and even failed mergers.”

Human capital – local laws and global issues

Similarly, as businesses go global, their overseas operations may face very different business cultures, talent attraction or retention pressures and an employee base with quite different expectations of their employer and HR team than at the corporate headquarters.

Accommodating these variables, HR is required to work through complexities and issues that have no specific geographic boundaries. Michael explains: “In the US, the dispersion of political ideologies between the pro-business national agenda of the Trump administration and several local (ie, state and municipal) preferences – to leverage corporate resources to drive social policies and/or more heavily regulate businesses – are beginning to generate divides in core business rules and expectations. State, and even city, regulators are beginning to create their own laws, rules and regulations relating to employment and human capital practices.

As an example, the City of New York has passed laws relating to the minimum amounts of paid sick leave that any employer, or any business that has any employees in the city, must follow and track for potential auditing by the local government. And those laws are different from the federal laws already in place (ie, the Family and Medical Leave Act).

“If you’re working out ways to address the relatively simple issues of how to recruit, retain and motivate people across the globe and in such diverse locations, when there are such uncertainties in terms of regulations, politics and economics, the challenge of doing it when physically removed from the culture and country is even more immense.”

Aligning global human capital strategies

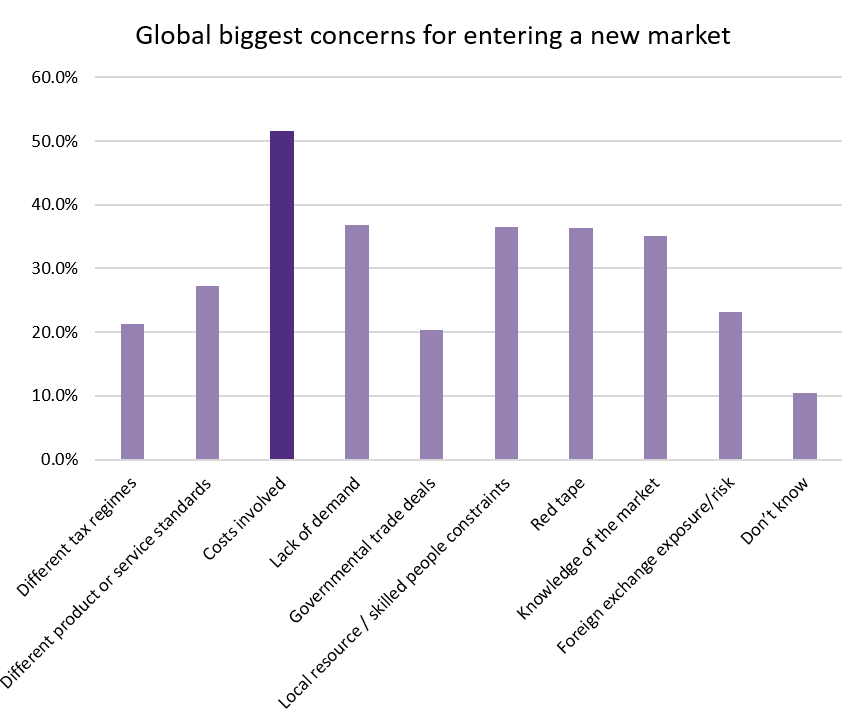

Grant Thornton has been following the evolving environment surrounding global human capital and HR closely and new figures from the firm’s International Business Report (IBR),[i] reveal that the biggest barriers or concerns when entering a new market are costs (including, but not limited to, personnel costs).

These barriers may be overcome with a deeper and more genuine understanding of the local environment and culture. Yet, in the same survey, executives state that they will be mostly seeking future talent from their local/home country (75.7%). This is a growing trend as businesses seek to manage costs in international mobility, attach return-on-investment to the financial cost of traditional assignment programmes and seek other strategies for achieving success in new market entry.

More than 90% of respondents indicated that offering competitive compensation and benefits packages to employees globally is important for the achievement of the company’s success. Yet the data also reveals a potential impediment to the success of the global expansion in that human capital teams, or those responsible for HR issues, tend to be centralised in the form of a dedicated corporate team (60%) and less than 20% have a hybrid model of a combination of a centralised team supplemented by local embedded resources.

As businesses expand and seek new markets, this approach will continue to challenge HR professionals to quickly uncover and comprehend a mass of new information relating to overseas local markets, customs, practices and costs to find the best resources for success. They will also need to design total rewards packages that can successfully lead to attracting, retaining and motivating the right people with the right skills for success.

So how can companies best manage this apparent disconnect – especially as it places inordinate pressure on HR to become expert in the environment and culture of new markets, from both the technical-rules perspective and in terms of the appetite for different compensation models?

Michael says: “The data suggests that going global is something that senior executives think is important, but that they are sensitive to cost in doing so, particularly on the employment side. Many of them also said they had centralised HR operations. So the challenge is figuring out ways to use a centralised approach to HR while at the same time learning about cultures, practices and costs of employment in these various jurisdictions. Businesses need to work out a way to get HR people up to speed quickly on what can be a very challenging business proposition.”

Regulation and taxes – avoid common pitfalls

There are many facets to global workforce issues when it comes to human capital. At the heart can be local as well as international employment law: how do you structure an employment contract and what employment regulations/protections will be in place?

Tax is another major consideration. Multinational tax challenges are among the most complex and potentially expensive issues facing companies bringing employees across borders and building operations in foreign jurisdictions. There’s also the risk of creating a permanent establishment (PE). The PE threshold test is part of many countries’ domestic tax laws, double tax treaties and the OECD’s BEPS Action Plan[ii], determining whether a business has sufficient activity in another territory to create a corporate taxable presence.

Then there are issues such as how much to pay, how to set up a payroll and social security contributions. Also, what benefits are typically provided to employees in that market and what do they receive from the state? Likewise, what’s the expected business performance and how do you incentivise employees to build up the business?

You may also need to consider if the employees with the right skills are actually available in the local market. Then, if they are, how you will persuade them to move from their current employer and, moreover, retain or end their employment in the future?

Local human capital solutions for complex global problems

In Monahan’s experience, one thing is clear: “The organisations that are successful confront the challenge by educating their central operations on culture by hiring people locally or using firms that are familiar with, or embedded in, specific geographies. The ones that fail are those that don’t take the time to educate HR on what’s going on in those communities.

“As a service provider, it’s incredibly important to have a truly global network of informed human capital professionals because as an increasing number of companies head into that space they’re going to have to rely on professionals who are on the ground to give them guidance on setting things up and have the experience of managing multi-jurisdictional challenges.”

So, although moving your business to a global level can be complex, it’s clear there are steps you can take to ensure a smoother transition – not least of which is drawing on local expertise, tapping into existing networks with the required experience, and starting your planning and cost analysis well in advance.

To find out more about how to align your human capital strategies with your global business objectives, contact Michael Monahan at michael.monahan@us.gt.com.

The expat is dead, long live the…?

It isn’t so many years ago that the common model for expanding abroad was to use expatriates – often on long-term packages or rotations. To set up a business in a different country, you would simply send somebody from your country to do it. However, this practice is markedly less common than it used to be.

Richard Tonge, managing director and global mobility services practice leader in New York, explains: “We’re finding that some jurisdictions are making it more challenging or expensive for companies to send expatriates. For example, there are countries in the Middle East where you have to hire a certain number of local citizens for every expatriate you send over to work for your company. Similarly, tax legislation that provided concessions for expatriates has, particularly in many developing countries, been replaced.

“It’s also often more difficult to entice expatriates, as they’re not necessarily as keen as they once were, or there’s less appetite for mobility within the company. Benefits packages on assignments have moved away from the generous levels seen before 2009 and some executives aren’t interested unless you really make it worth their while. It’s possibly a reflection of the instability of the global market, but it means the cost of hiring and managing of an expatriate often remains higher than hiring locally.”

Michael Monahan cites an example from the US higher education community: "One challenge universities face is that their brand and academic reputation are integral to their success. If they want to establish a campus in Rome or Qatar, for instance, how can they ensure the quality of education reflects their standards? This requires having one of their senior staff members set up the new location to maintain the university’s academic reputation and standards."

“They don’t want to hire people locally just because they have to, as new hires must be qualified and maintain the university’s quality and academic standards. The solution was to recruit locally but require new hires to work in the US for 18 to 24 months. This allowed them to learn the university’s approaches and standards from those most familiar with them. The individuals returned home better prepared, focused on preserving the institution’s global academic reputation.

“Finding different ways and solutions to assist with achieving organisational success is a big part of our business and the solutions that we offer.”

References

[i] The Grant Thornton International Business Report (IBR), launched in 1992, provides insight into the views and expectations of more than 9,600 businesses per year across 36 economies.